The year-end audit 2024

Wrestling with Die with Zero seriously when the costs of aging are unknowable

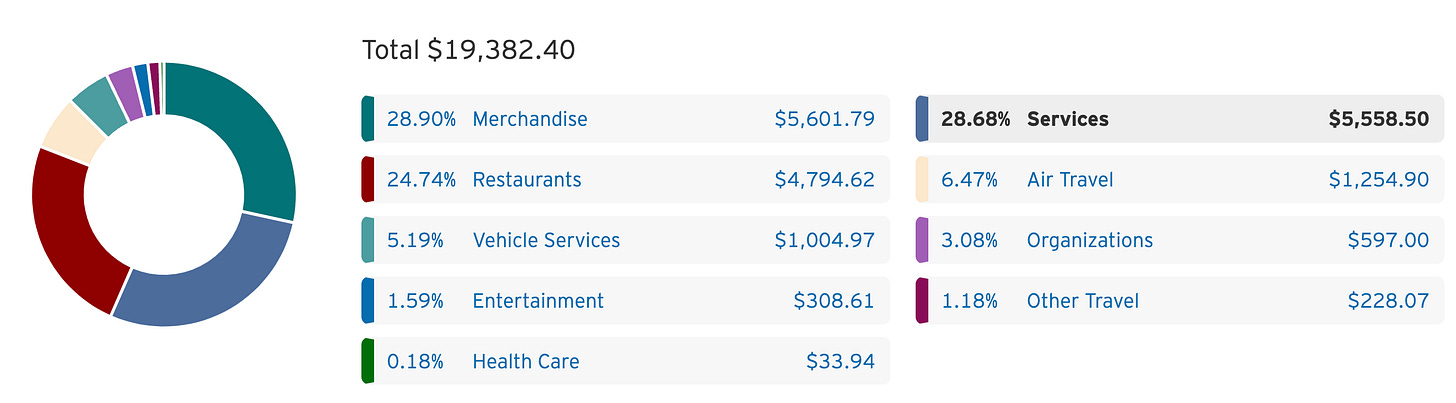

As is annual tradition, in December I publish my personal budget. It’s my accountability to what I’m spending. You can see my 2023 year end budget here and it has links to the previous ones. So without further ado, this is my credit card spending up for the first 10 months of the year:

$24k of credit card expenses. The above is $20k in 10 months, so for convenience sake, I extrapolated $2k a month to $24k the entire year.1 (You don’t have to worry about me participating in more consumerism during the holidays haha) So this year, I spent 20% more than the previous year:

Services are mostly household stuff: electricity, water, internet, cell phone bill, car and home insurance. Also business subscriptions for School of Financial Freedom like Discourse, Squarespace etc., so some of this is deducted as business expense.

Restaurants: my major “fun” expense. After years of documenting this, I’ve learned to accept that I spend more than $100 a week on restaurants. That sounds crazy to me, but that’s the point of an audit: to see the truth of yourself.

Merchandise: Mostly groceries. Some Amazon purchases, some of that for the house, some of it pure consumerism.

$500 per year on on another credit card which has trash autopayments on it.

I amortize my annual home maintenance as $3,000 per year. As FF alumni know, I don’t have a mortgage, thanks to younger Douglas saving and buying a home in cash. But if you have a house, you need to pay for homeowners insurance, property taxes and utilities (which I included in the above credit card expenses). You need to reserve money for home maintenance, even if you don’t have a mortgage. I spent very little on the house this year, mostly hardware store purchases. The universal recommendation is budgeting 1-4% of the value of the house for maintenance, which does not include renovations, which is consumption.2 This means if your house has 5% “home appreciation” every year, but you have to spend 2% in maintenance, after 3% (or more) of inflation, you are not gaining any “value” in the house. That's why you need to be careful about “appreciation” as you account for real estate in your nest egg. The numbers are worse if the housing market stays flat or drops. Portland has not achieved 5% real estate growth in a few years, so I and other people are actually losing money on the value of their home in real dollars.2

I paid $5000 in property taxes this year. This keeps going up.

So all in all, I estimate I spent about $33k this year in normal expenses, which is the same as 2023 because I didn’t make charitable donations this year. I’ll detail why in a future post.

Trying to die with zero

I’ve mentioned the concept of Die with Zero in last year’s post and to this year’s FF1 cohorts. But I started taking it seriously after watching this video, which really threw me for a loop.

I’ll explain it in my own words: the majority of Americans will hit retirement age without enough income. That’s a tragedy of both structural inequity and poor personal planning. But the large minority of Americans who have enough at retirement age will actually die with more assets than they retired with.3 According to Perkins, that’s a waste of life energy, particularly life energy in the best years of life. He believes the living the best life requires a combination of money, time, and health, so we should be timing our spending during the peak periods of health, which he believes are generally between ages 26-35.4 As we get older, we will spend less money, an 80 year old naturally wants to do less things than a 40 year old.5 So we don’t need to save as much as we do when we are younger and healthier.

Perkins addresses the objections that say one should save the traditional 25x cushion for when you’re not earning income anymore. Those objections mainly center around:

Saving for health care costs. Perkins points out that most people don’t actually use that much money for end of life health care and those who do, the last days, weeks, months of out-of-pocket expenses are too high in America anyway6, and

Leaving something for inheritors. Perkins cites statistics that show that, due to our extended longevity, the average inheritor receives it at around age 60. That is not as useful as getting an inheritance at age 30. He thinks you should give to your children while they are younger, so they can buy their first house, raise their children, or enjoy their lives at the peak of their health and energy. Giving it to them when they are close to retiring themselves isn’t as helpful. And if you plan on giving your money to charity, it’s better to do meet the needs of today than the needs of tomorrow (or let them be eaten up by your health care costs).

Anyways, Die With Zero has challenged me because he points out that, if I have 1 million dollars now at age 52, it doesn’t make sense to still have more than a million dollars at age 82 or, God forbid, 92. It would be better to draw down my wealth, either on myself or on the things I care about while I’m still alive.

Confronting money scripts

Of course as anyone of my former students know, it’s about money scripts. My money vigilance money script that allowed me to accumulate a nest egg for 20 years and maintain my wealth for the last 10 years without working. I can live happily on $32k a year and have enough assets to fund that. When I put my numbers into a Die with Zero spreadsheet, I would have to spend $70,000 a year, twice as much than I spend now. That would run counter to the status identity I built as a frugal person. It’s something I’ve been digesting for over a year now. I’ve begun to see the Die with Zero mantra as a Richard Rohr-ian second-half-of-life letting go, a surrender of the ego.

I encourage you to run your own Die with Zero numbers. Here is an explanation and spreadsheet.

Imagining spending twice as much money as I do now is disorienting. Both my needs and desires are met at $32k, so am I going to find $32k more of desires? That runs counter to my beliefs in Quaker voluntary simplicity, Buddhist wheel of samsara, and Stoic internal focus on happiness. I genuinely believe that spending more money isn’t going to make me happier. I could give an extra $32k a year away, but that feels dangerous. I’ll dive more into that below.

But I’ve taught FF1 long enough to know that our justifications and beliefs about how we earn, spend, and invest money conveniently match our money scripts. I’ve had a bunch of reasons/excuses for not spending. For example, my main excuse is the carbon emissions issue. I’ve covered the environmental issues many times in this newsletter, but my spending isn’t only about me, it’s also about not increasing my load on the planet. But I’m also seeing with increasing clarity that I’ve used to carbon argument as an excuse not to spend:

I’ve argued before that any spending eventually becomes carbon emissions, which may be conceptually right, but silly in practice.7 Spending $500 on a plane ticket is a more carbon-polluting activity than getting five $100 massages, even if the masseuse will eventually spend that money on a $500 plane ticket.

In FF1, I make the argument that buying expensive things is pointless, the material difference between a $25k Toyota and a $50k Lexus is negligible. You’re not actually buying $25k more of actual value, what you’re actually buying is $25k more of status, and these tiny-details upgrades are simply there to justify it. But the embodied carbon between a $25k Toyota and a $50k Lexus is negligible as well.

There are plenty of things to spend money on that are socially just, economically equitable, and low carbon. For example, I’ve begun to spend money on a house cleaner. I’ve spent years poo-pooing the idea of a housecleaner, because my class identity is someone who does not have others clean my house for me, I’m not one of those people. And while the house is definitely cleaner, I’m not sure I value it enough. But by getting my house cleaned, I’m providing someone with income, letting them meet their financial needs. I’m still working through that.

If I could to add a modernized element to Buddha’s Eightfold Path, it would be “right spending.” The main principle would be preferencing labor over capital. Spending money on services is less environmentally damaging, more socially just and more economically equitable than buying things. When you buy services, the profits go to a real person. When you buy an iPhone, or a car, or a plane ticket, profits go to a corporation (i.e. a fake person), a corporation that is destroying some portion of the planet to provide you that thing. You’re rewarding capital for destroying our organic container.

So when I think about spending more money, I’ve been planning on how to spend it on expertise and labor. For 2025, I’m planning on spending money on:

Music lessons. I’ve picked up guitar and piano in the last year and it’s been revelatory. I never thought I enjoyed music as much as others seem to. What I’ve realized is I like playing, especially with others, more than I like watching. I’ve learned that I have a strong preference to participate in an activity over watching it (like sports or sex haha).

Renovations. I’m moving houses in January (my current house still for sale) and I’m doing renovations on the new house. Probably a future post on that.

Health care. As Bill Perkins points out Die with Zero, spending money when you’re younger on health care, including physical fitness, has a much higher ROI than spending $50k a night on end-of-life, like he did with his father. Will I spend money on a personal trainer, or even a gym? I dislike strength-training, even though that’s the thing that will extend my health the longest, so that’s more than a financial question.

Suggestions? I welcome reader’s concrete suggestions to how to spend money in socially just and environmental sane ways. If I get enough, I’ll publish them.

Like I said before, I genuinely believe that spending an extra $32k a year on myself would not make me happier (thanks Buddhism, Quakerism, immigrant parents). My material needs are completely met and my desires simply don’t run that high.

But it makes no sense to keep accumulating, or even maintaining, in the second half of life. As per Jung and Rohr, a lifecycle spirituality would gradually collect, and then distribute, possessions over a lifetime. You have to build, and then let go. As Eckhart Tolle wrote, repeating the wisdom of all the great cultures, “The secret of life is to 'die before you die'—and find that there is no death.” That is the practice of spiritual freedom. I believe Dying with Zero is a sneaky practice of that.

Dying with zero, alone

I could Die with Zero by giving an extra $32k a year away to charity, but that feels really dangerous. All money scripts are a projection and protection of the ego. My money scripts believe that a nest egg buys me security. Other people’s money scripts believe that money buys respect. Or that money buys happiness.

My frugality hasn’t been only a moral stance to environmental collapse, it has been has been a guardrail for safety. Again, I’m a child of immigrants, immigrants who lost everything fleeing from the Communists. You don’t spend money frivolously after that happens.

Safety shows up in other ways. I’ve been texting Vicki Robin about it because one of the things we’re both worried about the issue of solo aging — people growing older without reliable support from adult children or other family. Baby boomers and Gen Xers, by choice or circumstance, are childless at about twice the rate of previous generations. According to AARP, about a third of people 50 and older now live alone and don’t have children, are estranged from their children or can’t depend on them or other family members for help. Millions more are married without children, which will mean eventually being on their own after a spouse dies.

Vicki told me that her savings give her a feeling of safety, a buffer against the terror of ending up mentally or physically disabled with no one to help her during what could be a slow, potentially years long, process of physical and mental decline before dying. Life without having money to hire help is untenable.8 Without a younger family member, we solo-agers will need someone to help with what Medicare calls the Basic Activities of Daily Living:

Bathing

Continence

Dressing

Eating

Toileting

Transferring

Imagine trying to go through life without being able to do even one of these. What if it lasts months? And you don’t have money?

Even earlier than the Basic Activities, we’ll need help with the Instrumental Activities of Daily Living (IADLs):

Managing finances

Preparing meals

Shopping

Doing laundry

Taking medications

Using the telephone

Performing household chores (e.g., cleaning, gardening)

Imagine trying to go through life without being able to do even one of these. What if it last years? And you don’t have money?

It’s important to note that never before did we need savings for these things; we all lived in intergenerational communities when the young took care of us when we got older, just as we took care of others before us. But now, as we’ve become more individualized, aging and dying are becoming solo endeavors. We don’t want to take care of others, even our own families, because it interferes with the other activities of life, like working and earning a living. So we hope to replace support from family with institutions. But those institutions not only lack the resources to adequately provide for us, they lack the soul to spiritually provide for us. We have an existential need to feel loved, necessary, and valued, way past our “productive” years.

So how do I take Die with Zero and the second-half-of-life letting go of my nest egg, my ego’s protection of itself through frugality seriously, while still taking my second-half-of-life’s actual, but unknowable, material needs? I would note that Bill Perkins is a finance bro worth roughly $500 million in his 40s (and has children), while Vicki just entered her 80s, with a lot less. Bill suggests that we can buy long-term care insurance, but I’m pretty sure he hasn’t done so himself; my research and most everyone I talk to says that long-term care insurance is somewhat like earthquake insurance: expensive and with enough qualifications that it won’t actually cover worse case scenarios. Even if long-term care covered support for the Basic Activities of Daily Living, I’m pretty sure it would not cover the Instrumental ones. You want to spend years unable to shop, cook, or do laundry and not be able to afford help doing so?

Bill has enough money and family that he can “self-insure” his way out of this. Vicki does not.

So if you don’t have $500 million is Die with Zero is full of shit? Is the answer to still stay as frugal as you can and give your remainder money away as you die? But what if letting go of your money is part of the surrender that dying before you die asks of us?

What much is enough? I want to see Perkin’s stat for elderly spending for the solo-aging. Because maybe frugality is less about the environment, and more about caring for the unknowable needs of your Future Self in a society that lacks familial care and continuity?

I have nothing resolved. I’m curious what you think. Run your own Die with Zero numbers and let me know where you end up morally and spiritually.

Looking forward to hearing from you.

2025 FF1 new year cohort

Want to get your long term finances in order in 2025? I’m teaching another Financial Freedom 1 starting in January. I’ve started a new policy: Register and pay for the course and if you finish, you can ask for 50%, 75% or 100% of your tuition back (your choice). I really love teaching this course; it’s meaningful for me to help people take control of their financial lives and live the life they were meant to.

Think of the money as a commitment device for you to do the work; from the lessons, you’ll easily make that amount up in a couple of months. The refund policy is just a further enticement for you to finish and a gift to start your financial freedom journey.

Consider signing up! Or share with friends or family looking to get their house in order.

I got two different “points” credit cards in November.

While stock equities continue to go up around 10% a year.

From the book: “(The Federal Reserve’s) most recent Survey of Consumer Finances (showed) that the median net worth for U.S. households headed by someone aged 45 to 54 is $124,200. American heads of household between the ages of 65 and 74 have a median net worth of $ 224,100, up from the $ 187,300 saved up by householders between 55 and 64. That’s crazy—people in their seventies are still saving for the future! … (H)ouseholders aged 75 or older is the highest of all the age groups: $ 264,800. So even with rising life expectancies, millions of Americans are on track to have their hard-earned money outlive them.”

“At the high end, retirees who had $500,000 or more right before retirement had spent down a median of only 11.8 percent of that money 20 years later or by the time they died… Retirees with less than $200,000 had spent down only one-quarter of their assets 18 years after retirement… One-third of all retirees actually increased their assets after retirement. Instead of slowly or quickly decumulating, they continued to accumulate wealth.”

For the personal finance nerds, he’s building on an economic concept called consumption smoothing, where you decouple your spending to ages when you most get the most out of spending (utility) from when you earn it, because you typically earn more later in your career.

Apparently in the financial planning world, you can divide your life into the go-go years, the go-slow years, and the no-go years.

“Some people never actually planned to spend all that money on life experiences but instead were saving for the unforeseen expenses of old age, especially medical expenses. It’s not just that everyone’s health declines as they get on in years, creating higher medical expenses toward the end of their lives. It’s also that the actual expenses are hard to predict: Will you need triple bypass surgery or years’ worth of treatment for cancer? Will you have to spend years in a nursing home?… (But) no amount of savings available to most people will cover the costliest healthcare you might possibly need. For example, cancer treatments can easily cost half a million dollars a year.

“If) expenses amount to $550,000 per night (as they did for my father’s hospital stay at the end of his life), does it really matter whether you’ve saved $510,000 or $50,000 or even $250,000? No, it doesn’t, because the extra $ 50,000 will buy you one extra night, a night that might well have taken you a year’s worth of work to earn! Similarly, $250,000 saved over however many years will get wiped out in five days… you can’t pay your way out of high-priced end-of-life medical care; since uninsured medical care is so expensive, it won’t make any real difference for the vast majority of us whether we save for it or not. Either the government will pay for it or you will die.”

“Even if I earn enough that I could save up for a few extra months of life in the hospital, I can’t see the logic in doing that: There’s a big difference between living a life and just being kept alive, and I’d much rather spend on the former. So I will not work for years to save up for a few more months on a ventilator with a quality of life that’s close to zero—or, depending on the level of suffering, maybe even negative. So instead of engaging in “precautionary saving,” as economists call the practice, I’ll let the cards fall where they may. We all die sooner or later, and I’d rather die when the time is right than sacrifice my better years just to squeeze out a few more days at the tail end.”

“Besides, it is much smarter to spend your healthcare money on the front end (to maintain your health and try to prevent disease) than to spend it at the end, when you get a lot less bang for every buck you spend.”

I was wrong on this one, Cedric. Public apology!

If you’re interested in Vicki’s reflections on these issues, subscribe to her Substack, the popular Coming of Aging. Examples here and here.

What your thoughts are about Daniel Kahneman’s end of life decision? I’m not advocating for anyone to take that path, but it seems that would be a way to plan for spending more when you are younger and allows one to not have fears of a slow decline without enough resources for hired help.

Some thoughts: you can use money to buy you care when you are older. It might be more soulless than a familial or communal set up, but it is guaranteed. If a more soulful future is what you want to create, you could begin to set up a life that is more familial and communal. Money can't buy us connection. But sharing our lives with others is a great way to start forming bonds, in my opinion. Giving your money to a charity where no one knows who you are doesn't create connection for you. But investing into the life of someone younger than you and sharing your resource with them will create what Matthew Engelhart calls "social equity". Because of how generous Matthew and Terces are, I genuinely want to see them taken care of, so if they were ever to need help as they get older I would be willing to use my precious time to make sure they were well. That's because I feel connected to them. They really care about helping me succeed and I feel their love and also desire for them to succeed. I am only speaking as a young person so I do not know what it is like to be older. I think making sure you feel safe is important to notice. I just think as of right now that being alone paying for others to do my basic needs sounds less appealing than being in a familial community having friends taking care of me (maybe with some help from my money when they are busy doing other things with their one and precious life).

So many people need resource and would be happy to have your extra $32k a year haha. But there are ways to give your money that creates a more connected life FOR YOU, so I understand why feeling into those options is so valuable.