I’m in the Bay Area right now. My mom/aunt Dora Ting passed in her sleep last week. The last two weeks of her life was me and her, 1-1, on home hospice. Just the two of us, with a nurse visiting a couple times a week. It was intense, beautiful, and difficult. As her colon cancer got worse, I massaged her to relieve her pain. I touched her more in the last two weeks than I have in my entire life. Things were said that should have been said years ago, the only words that really matter in life: Thank you. I’m sorry. Please forgive me. I love you.1

Words that might have been said before, but took on far different meanings now.

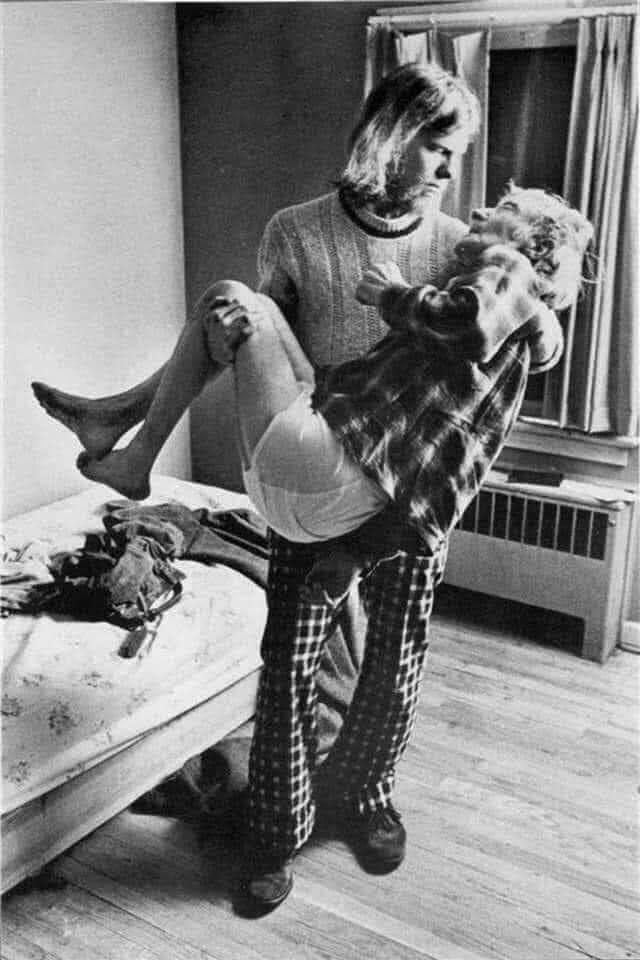

She got a good death: in her marital bed, in her home of 40 years, in peace, without pain. I’m honored and so grateful that I was able to give that to her. This is a photo of her two years ago, before her illness.

I read this on Vicki Robin’s FB feed and it described the final days better than I can. All credit goes to the original author/poster.

Fear of Your Parents' Old Age

"There is a break in the family history, where the ages accumulate and overlap, and the natural order makes no sense: it’s when the child becomes the parent of their parent."

It’s when the father grows older and begins to move as if he were walking through fog. Slowly, slowly, imprecisely.

It’s when one of the parents who once held your hand firmly when you were little no longer wants to be alone.

It’s when the father, once strong and unbeatable, weakens and takes two breaths before rising from his seat.

It’s when the father, who once commanded and ordered, now only sighs, only groans, and searches for where the door and window are—every hallway now feels distant.

It’s when one of the parents, once willing and hardworking, struggles to dress themselves and forgets to take their medication.

And we, as their children, will do nothing but accept that we are responsible for that life.

The life that gave birth to us depends on our life to die in peace.

Every child is the parent of their parent's death. Perhaps the old age of a father or mother is, curiously, the final pregnancy.

Our last lesson. An opportunity to return the care and love they gave us for decades.

And just as we adapted our homes to care for our babies, blocking power outlets and setting up playpens, we will now rearrange the furniture for our parents.

The first transformation happens in the bathroom. We will be the parents of our parents, the ones who now install a grab bar in the shower.

The grab bar is emblematic. The grab bar is symbolic. The grab bar inaugurates the "unsteadiness of the waters."

Because the shower, simple and refreshing, now becomes a storm for the old feet of our protectors.

We cannot leave them for even a moment.

The home of someone who cares for their parents will have grab bars along the walls. And our arms will extend in the form of railings.

Aging is walking while holding onto objects; aging is even climbing stairs without steps. We will be strangers in our own homes. We will observe every detail with fear and unfamiliarity, with doubt and concern.

We will be architects, designers, frustrated engineers. How did we not foresee that our parents would get sick and need us?

We will regret the sofas, the statues, and the spiral staircase. We will regret all the obstacles and the carpet.

Happy is the child who becomes the parent of their parent before their death, and unfortunate is the child who only appears at the funeral and doesn't say goodbye a little each day.

My friend Joseph Klein accompanied his father until his final moments.

In the hospital, the nurse was maneuvering to move him from the bed to the stretcher, trying to change the sheets when Joe shouted from his seat: Let me help you. He gathered his strength and, for the first time, took his father into his arms. He placed his father's face against his chest.

He cradled his father, consumed by cancer: small, wrinkled, fragile, trembling. He held him for a long time, the time equivalent to his childhood, the time equivalent to his adolescence, a long time, an endless time.

Rocking his father back and forth. Caressing his father. Calming his father. And he said softly:

I'm here, I'm here, Dad! "What a father wants to hear at the end of his life is that his child is there."

I love you, Dad, wherever you are, I always think of you, I will never forget you...

I’m not sure what any of this has to do with money, other than because I didn’t have to work, I got to spend months of her last year with her. Money is the gift of time. I wrote about my dad/uncle’s passing this summer, at the age of 64 from ALS:

He was 64 and I was 42. I thought that we had 20 more years together. We didn’t.

We had none.

Priorities matter. The tail end matters. Quality time matters.

Because we might not even get it.

I remember that I didn’t spend his last year with him because I “had to work.” Actually I got FMLA to spend more time with him, but he, typical Asian immigrant, wouldn’t let me come stay because it would “hurt my career.”2 Ha! What a joke And to my lasting regret, I obeyed him. Because I secretly wanted to avoid watching him die.

I used work as an excuse from being present for him. It’s easier to focus on “advancing” and “doing well” than to see him slowly get shut into his body. What bullshit. I used work as an excuse not to enter deep time. Dad, I’m sorry. Please forgive me. I love you. Thank you.

I used busyness as a cop-out from entering my deepest grief.

Maybe you have too?

There’s an ancient Chinese story about a king, wanting to know to true wisdom,3 has his soldiers search for a rumored Taoist master hiding in the mountains in a cave. After hunting for a long time, the soldiers find the master, drag him to the palace, and place him in front of the king. The king asks, “OK, you are rumored to be the wisest man on earth, what do you have to tell me?”

The master replies: “King dies, prince dies, prince’s son dies.”

The king, furious, yells for his soldiers to behead him. The master, having reached total equanimity, nods and accepts his fate. The king, recognizing the master’s lack of fear as someone awakened, asks, “Wait, what did you mean by that?”

The master says, simply, “This is the natural order of things. For the prince to die before his father is a tragedy. For the prince’s son to die before the prince dies is a tragedy. The king must die before his son.”

The king instantly realizes the wisdom, comes down from his throne, and bows to the master on his knees. And lets the master go.

Death is the most natural thing. Giving you parent a good death is the most natural thing. Miss it and you miss the whole thing.

As I’ve gotten older, I’ve become less rebellious, more traditional. Such is the natural order of things. I write a lot about Taoism in this blog. But the natural counterweight of the freedom of Taoism are the duties of Confucianism. The central obligation in Confucianism is filial piety: a moral obligation of respect and care for one's parents. Every regret I have towards my parents is from a failure to do this.

But in the end, I was there for my mom. I held her for a long time, the time equivalent to my childhood, the time equivalent to my adolescence, a long time, an endless time.

I gave her the death she wanted: in her marital bed, in her home of 40 years, in peace, without pain.

To bury your father and your mother is the natural order of things.

Every child is the parent of their parent's death. Don’t miss it.

Dark grace.

As a guide to my own financial freedom, I ask myself a question from a fantastic Heidigger documentary Being in the World. I give it to you now: search your experiences for times when you could say:

(1) There is no place I would rather be.

(2) There is no one I would rather be with.

(3) There is nothing I would rather be doing.

(4) And this I will remember well.

I missed my dad’s death. I was not going to miss my mom’s.

When the time came, I knew there was no place I would rather be.

There was no one I would rather be with.

There was nothing I’d rather be doing.

And this I will remember well.

Goodbye mom. Thank you. I’m sorry. Please forgive me. I love you.

Dying is the most important thing you do in your life. It’s the great frontier for every one of us. And loving is the art of living as a preparation for dying. Allowing ourselves to dissolve into the ocean of love is not just about leaving this body; it is also the route to Oneness and unity with our own inner being, the soul, while we are still here. If you know how to live and to love, you know how to die. — Ram Dass

Postscript: I learned so much about the dying process. For all of human history, we faced death our entire lives: children saw grandparents die in their homes. Now we sanitize it and remove it into institutions. We’ve removed death from our consciousness, because we fear it and it would make capitalism run far less efficiently if we were aware of our duties to our dying.

I think of myself as a relatively well-educated person and I knew nothing about how to care for a dying loved one. How sad that is true for most of us. I’m so grateful for my friends who shepherded me through the process. Rishi, who is a trauma surgeon, who walked me and mom through what would happen in her final days. Katie, who is a hospice social worker, who guided me through understanding the resources I needed and checked in me every day. Jessica, who guided both her father and mother in their final days, who listened to me in the moments of terror. What do people do if they don’t have trauma surgeon/social worker/death doula friends? I’m so grateful for them, the home hospice team, and Medicare, who paid for this. Whatever gripes you have about the healthcare system, remember there is grace in there too. Although I was alone, in those final days with my mom, there was a community, a profession, and a social safety system supporting me. I was being held in the Light.

I hope you get this too.

I may take a break from writing this newsletter for a while, a sort of grief sabbatical (it’s a sick society that makes people have to go back to work after 3 days of “bereavement leave.”). I leave you with a snippet from 10 THINGS YOU NEED TO KNOW ABOUT APPROACHING DEATH, by Barbara Karnes, RN:

1. Dying is not a medical event. It is a personal, social, communal experience. It is not about endless treatments but about living the best we can within the limits of our body and disease.

5. A terminal illness is a gift of time. Most people don't know when or how their death is coming. When the doctors tell us they are having a hard time fixing us, as difficult as it is, they are giving us a gift, a gift of time. This is the time to do and say what we want said and done.

Dying is not a medical event. It is a personal, social, and communal experience.

Death is the most natural thing. Miss it and you miss the whole thing.

A terminal illness is a gift of time. Don’t miss out out on grace.

Take good care. Of yourself, and those around you.

Ho’oponopono: https://hooponoponomiracle.com/iloveyou-imsorry-pleaseforgiveme-thankyou-mantra/

I think the real issue is he didn’t want me to see him deteriorate.

This would never happen in America.

Douglas, I'm very sorry for your loss. My deepest condolences to you. Thanks for sharing your touching reflections and please take good care.

My deepest condolences for your loss, Douglas. Thank you for sharing your heartfelt perspective and experience with us. I’m walking beside you on this journey of parenting our parent’s death. You are not alone. Wishing you comfort and peace 💛