No one wants to get rich slowly

Care for your future self by saving and investing in the future. Care for future others by consuming less.

We’ve had a long stretch of the spiritual/emotional side of money, so this week I wanted to get back to the more concrete, practical side. So I thought I’d talk about one of my favorite FF topics: the miracle of compound interest. Trigger warning: this contains middle school math!

An apparently true story of the world’s richest man, Jeff Bezos asking the second richest man, Warren Buffett: "You are the second richest man in the world and yet you have the simplest investment thesis. How come others didn’t follow this?"

Warren Buffett replied: “Because no one wants to get rich slowly.”

Another perspective, from one of my FF students:

I’ve spent some time in the esoteric/magic/witchcraft world, and I came at it from a real skeptical lens. Magic seemed so improbable, like if someone could just wave a wand and change the world, then why weren’t these witchy people more successful? If fortune tellers could see the future, why didn’t they pick the lotto numbers so they don’t have to work out of a ramshackle house on the bad side of town?

The thing I came to understand about magic is that it is very much real, but it doesn’t work like a Disney film. It is usually mundane and gentle and simple. It’s subtle shifts in attitude and awareness. It’s keeping your eye out for what what Tarot card could mean in your life today. It’s paying attention and noticing when you actions aren’t in line with your intentions.

FIRE seems pretty similar for me. Coming into it, I was hoping to find that one simple trick where I just do it and everything is better. The reality is that it is simple and mundane and kinda boring. The times when it is really striking and amazing, it’s usually not that amazing when you dig into it… Saving as much money as you can is the best way to save a lot of money. That’s it. It’s kinda boring, but it is real, and given a lack of magic wands, it’s pretty much the best option out there.

Compound interest: Best friend or worst enemy

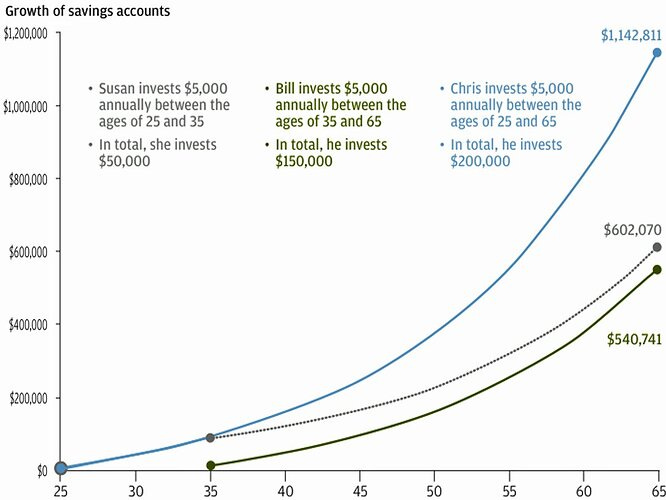

In FF1, we study the miracle of compound interest. Compounding interest is your best friend if you’re investing your money and your worst enemy if you’re borrowing. Every dollar you spend today is several future dollars forgone. Every time you buy something on credit (that includes your home, your education, or regular credit card debt), you’re spending multiple future dollars for each dollar you borrow. Conversely, when you decide not to spend and instead invest a dollar, it becomes 10 future dollars in a wealth snowball. Compare Susan, Bill, and Chris below (source).

When you look at Susan, Bill, and Chris, remember that this is $5,000 a year. Cut $410 a month from your housing, transportation, or bullshit spending and then invest, and you will retire a millionaire. Similarly, make $410 extra a month, keep the current level of consumption and invest, and you get the same result. Also worth noting: invest for 10 years when you’re younger, and it’s the same thing as waiting and investing for 30 years when you’re older.

The biggest mistakes people make: (1) buy investments that don’t offer high enough returns, like money market funds (2) panic when the market hits a bad patch and sell when it drops, or (3) buy into risky and shady investments due to greed and the promises of getting rich quick.1 As I’ve taught FF2 in the last 6 years, any number of students have wanted to skip normal, slow investing to sink their money into crypto, NFTs, or GameStop. Needless to say, most of them (mostly men) lost money. That’s why they’re called get-rich-quick schemes. They didn’t have the patience to get rich slowly.

You don’t need to be a rocket scientist. Investing is not a game where the guy with the 160 IQ beats the guy with a 130 IQ. Rationality is essential. — Warren Buffett

But the major reason I was able to retire at age 42 was (along with my spending $25k a year) was I invested.2 You can see when I started investing around 1992, when I was 20 years old, the S&P 500 was about 1,000. Today, June 2023, it’s around 4200. The entire time, up until I “retired” in 2014, I just kept investing everything I had earned after my $25k annual consumption, into this:

Obviously you have to have a long-term view of things to keep investing. If you look at the chart above, all sorts of interesting things happened: the market peaks around 1999 and drops and does not recover until 2013. In 2008-2009, the market drops by 60%.3

Charlie Munger once said, “The first rule of compounding: Never interrupt it unnecessarily.” Brilliant statement but very hard to put into practice. When times are great, people want to invest. When times are bad, people want to sell. The secret to all of it is to take the long view and be consistent: invest when stocks are high andinvest when they are low.4 Don’t interrupt compounding and don’t think you’re smarter than everyone else. You are not. Riding the miracle of compound interest means looking at your personal finances in terms of decades, not years.

It reminds me of the quote I referenced last week from Jesuit mystic Teilhard de Chardin. Compound interest is not God, but perhaps it gives you inspiration not to rush things.

Above all, trust in the slow work of God.

We are quite naturally impatient in everything to reach the end without delay.

We should like to skip the intermediate stages.

We are impatient of being on the way to something unknown, something new.And yet it is the law of all progress

that it is made by passing through some stages of instability—

and that it may take a very long time.

A choice between spending today or tomorrow

My friend JD Roth runs the popular website Get Rich Slowly. He says:

“Saving is not sacrifice. When you save, that money is still spent. But it’s not spent on a Mercedes or a big house. It’s spent buying your future. The opportunity cost of starting late, a foolish purchase, or a bad investment isn’t lost income or lost compounding. It’s lost time—lost experience and lost life.”

And spending a dollar now is choosing not to spend several future dollars in the future. So frugality and investing aren’t self-denial; they are sharing something with your future self.

Saving and investing for the future now means giving up something in the present. Spending a lot now means sacrificing a richer tomorrow. That’s why making wise, value-aligned purchases and forgoing thoughtless, unmindful, or wasteful consumption makes so much sense. As the writer Kevin Kelly says:

“Greatness is incompatible with optimizing in the short term. To achieve greatness requires a long view. Raise your time horizon to raise your goal.”

If Vicki Robin is right, money and life energy are interchangeable. You exchange your life energy for money and vice versa. That means the miracle of compound interest is interchangeable with life energy too. Quite simply, you buy more future time by saving now. If you want more future life to do the things you want, you have to increase the present savings rate and rate of return of your current life energy. What you’re doing is balancing the present and future consumption of your life energy. There’s no such thing as not spending. It’s a question of when.

Almost everyone, when they get old, realizes that they didn’t save enough when. Two-thirds of Americans ages 60–79 surveyed wished they should have saved more when they were working: 66.6 percent said they would save more if they could re-do their earlier life. Only 1 percent wished they had saved less and enjoyed their lives more. (Source) As Tennessee Williams said, you can be young without money, but you can’t be old without it.

Two reasons why I’m a bit cautious of Paula Pants’ suggestion for semi or mini retirements. First, if you take semi/mini retirements, your life energy in the form of money doesn’t compound, meaning the stress and worry of capitalism remains in the background for your entire life. Second, you never build a cushion for when you get older when perhaps you cannot work or the employers/customers don’t need you anymore. With AI and increased automation, that’s a worry for nearly everyone. Second, when you build a nest egg of 25x, your financial resilience means economic crashes like 2008 or 2020 matter a lot less to you.

Another metaphor I use a lot (especially in FF2) is “the seasons of your life.” Think about life as starting in spring, moving to summer, and then slowly transitioning to fall and winter. Spring is when you plant things. You tend to them as they grow in the summer. In the fall, you begin harvesting and saving up for winter. Think about your career and lifelong relationship with money as your financial garden. When you’re young, you’re planting seeds: investing in your career and investing money. The summer is a long stretch where your working skills and investments grow and bloom in anticipation for your later years, where you will live off the fruits of your labor. The point is: you have to plant seeds and tend to what you grow now. Otherwise, there’s nothing to harvest in the future.

But, Douglas, I don’t want to participate in the stock market

I get a lot of pushback when I tell people that they should invest. “But Douglas, I don’t want to participate in global capitalism and the continued destruction of this planet and exploitation of the poor.” Some may accurately point out that the miracle of compound interest actually depends on the continued destruction of this planet and exploitation of the poor. While I don’t have a perfect answer to these objections, this is what I say:

You are participating in the stock market. You buy things, right? That means you are participating in global capitalism and the continued destruction of the planet and exploitation of the poor. But most people don’t want to think about that as they consume. Example: so many people in progressive circles refuse to invest in oil companies because they are contributing to climate change. But those same people use fossil fuels in the form of planes, cars (their own or Uber/Lyft), and public transit. So why would you hold an ethical line on your investing and not on your consumption? Your consumption has far more impact on the world than your investing. When you buy a stock in Exxon, you are buying from another investor; Exxon never gets any money from it. When you buy gas from Exxon, you are giving money and profit to the company. That money and profit is what drives the stock price. Extend that to the phone in your pocket. To most things you buy at the grocery store, etc etc. So in essence, you are willing to destroy the world through consumerism but not investing? Your consumption has a much greater effect on the world. Honestly, I think your refusal to invest is just posturing. You are investing, other people are just getting the profits. That’s a bad choice all around.

You are participating in the miracle of compound interest. You can’t help it; it’s called inflation. When I was in high school in the 1980s, gas cost about $1 a gallon. Now it costs $4 a gallon. Over time, your money decays; it buys less over time. When inflation is 3%, your money halves in 25 years. When inflation is 7%, like it was last year, your money halves in 10 years.5 No matter the rate, the dollar in your pocket is worth less than it did last year. There is no not-participating in compound interest. You have to keep earning the miracle of compound interest just to stay even.

Investing: It’s kinda boring, but it is real, and given a lack of magic wands, it’s pretty much the best option out there.

Loving your future self

I don’t have morally perfect solutions to the problems of the world.6 But I’m reminded of Fred Rogers:

Love isn't a state of perfect caring. It is an active noun like struggle. To love someone is to strive to accept that person exactly the way he or she is, right here and now.

I think you have to love the world, as it is, with all its flaws. And with all yours too. I’m guessing you consume imperfectly, like fly on planes for vacations. I suggest you invest imperfectly too. The strategy that I believe that is most ethically palatable is to invest, to leave money for your future self, while consuming as little as possible, to leave as much of the planet for future others.

And here’s the secret, if you limit your participation in the consumption side of global capitalism, you don’t need to participate on the investment side nearly as much. Using the 25x rule, my living on $25k of living expenses per year means all I need is a nest egg of $625k. But if I spent $100k a year, I would need to get to a $2.5 million nest egg. Spending less means needing to invest less. Todd Tresidder of FinancialMentor.com describes it this way: “Decide the level of comfort that’s right for you. There’s no right or wrong. You just have to be willing to pay the price for the lifestyle you choose.”

I actually think there is a right and wrong. You have to care for your future self and future others. And worrying is not caring. As Mr Rogers says, caring is an active noun, not an emotion. Care for your future self by saving and investing. Care for future others by consuming less. We have to leave something, other than ashes, for others.

In FF2, we talk about investing. If you don’t want to take that course, here’s the quick version: How to Invest: an essential guide

The American stock market has done very well in the last 30 years. No guarantee it will outpace the rest of the world, but if in 1990 you had invested $100 in the S&P 500, an index of American companies, you would have about $2,300 today. If you had invested that $100 in an index of non-American rich-world stocks, you would have about $510 today.

Interestingly, when I reached FIRE in 2014, the market had just gotten back to where it was in 1999. Huh.

If you are a nerd, you can dive into dollar cost averaging. In essence, when you put in a consistent amount of money into the stock market monthly, you end up buying more stock when they are cheaper than when they are more expensive.

The Rule of 72 is helpful if you want to know how quickly your money doubles, or halves.

There is a phrase: there is no ethical consumption under capitalism. I’m not sure there is ethical investing under capitalism either (despite “socially responsible investing” which is its own topic). But I do know most people who complain about global capitalism and climate change consume more than those who don’t (I wrote a post about it).

Great stuff and solid advice!!

Yet another splendid essay Douglas...you continue to pass on wonderful wisdom. Thank you!