I'm losing my taste for meat

Emotional ethics, an increased intimacy with reality, and kinship culture

I’m losing my taste for meat.

It’s not because farm animals cause 25% of greenhouse gases. Or because factory farming is a deeply unethical way to treat other living things. Although both are true.

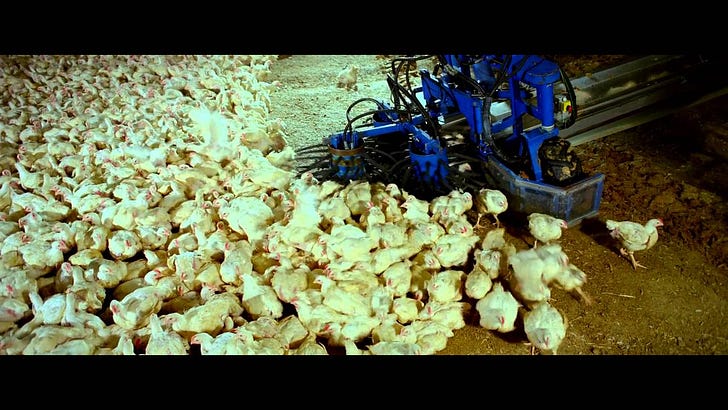

It’s because on New Year’s Day, I watched the movie Samsara. In it, there is a 10 minute clip showing the industrial factory farming system:

Ever since watching the above, eating meat has given me less pleasure. I’m still doing it, like when I’m a guest or sharing a meal at a restaurant with a friend. But it’s been tasting metallic and I’m not enjoying it.

A simple truth in life: most of us wouldn’t do what we do if we saw the consequences. I mean see them. Enter a factory farm and many of us would stop eating meat. That’s why the U.S. has made it illegal to film what happens in a factory farm.1 Instead we get cute ads.

That applies to a lot of other things too. Which items that you bought this year would you have bought if you saw the supply chain of it? Americans buy 170 million cell phones a year. No way we would do so if we saw the beginning of the supply chain, rare earths mining in African conflict areas, to the end, toxic disposal in India. The average American buys 67 items of clothing a year, once every five days. Would they do so if they saw a clothing factory in Bangladesh? Instead we get ads:

There’s intellectual ethics and there are emotional ethics. Few people follow intellectual ethics. There’s a difference between knowing something and feeling it. Participating in capitalism requires a near-total avoidance of the truth of how things are produced. We might know it intellectually, but better not feel it emotionally.

An increased intimacy with reality

When I interviewed for my Franciscan spiritual director program, Sister Mary Jo asked me why I, a non-Christian, wanted to join. I told her that I’m not a Biblical scholar, but this one Gospel story caught me, where Jesus tells the disciples they will have a seat in the Kingdom of Heaven:

… because when I was hungry and you gave me something to eat, I was thirsty and you gave me something to drink. I was a stranger and you invited me in, I needed clothes and you clothed me, I was sick and you looked after me, I was in prison and you came to visit me.

The disciples ask him:

“When did we see you hungry and feed you, or thirsty and give you something to drink? When did we see you a stranger and invite you in, or needing clothes and clothe you? When did we see you sick or in prison and go to visit you?’

And Jesus answers:

“Whatever you did for one of the least of these, you did for me.”

I told Sister Mary Jo that again, I’m not a Biblical scholar, or even a Christian. But I’m interested in the places where I avoid my homeless neighbor, where I don’t give money to the person who needs it more than me, where I turn away from someone who is suffering and needs help. Mother Teresa wrote that living a contemplative life in the world meant seeing and adoring the divinity in everyone, especially in the “distressing disguise” of the lepers, the poor, and the dying.

It’s much easier to eat factory meat, buy clothes, or use cell phones, if we separate ourselves, both physically and emotionally, from the reality of how it’s done. It’s much easier to shunt away the sick, poor, and dying to places we don’t have to see. Sickness, old age, and dying are what the Buddha’s father tried to shield his son from. And awareness of those very three things is the human condition we’re trying to run away from. In contrast, my friend Annie told me that the goal of her spirituality was an increased intimacy with reality. I love that word intimacy. It implies both knowledge and love of something. Spirituality is an increased knowledge and love of the world.

Possession rich and time poor

In the wonderful book Four Thousand Weeks: Time Management for Mortals, journalist Oliver Burkeman talks about how our overachieving/high-speed living is a way to avoid what’s going on inside ourselves. We mindlessly work and consume to numb intolerable emotions.

Maybe I’m not doing what I’m supposed to be doing with my life. I’m not sure I like myself. I’m scared about illness, old age, and death. It’s easier not to think about these things. Keep running on the work/spend treadmill. If we think we’re “conscious,” maybe we include buying some “spiritual” products:

“Time is the country in which all spiritual practices live and breathe. To pray, to meditate, to cultivate mindfulness, compassion, and care requires time and attention. If we have not stopped long enough to sow and cultivate these seeds, a fruitful spiritual practice will be very difficult indeed. So the marketplace, sensing our desire for things spiritual, offers to sell them to us. Simply buy this new self-help book, this yoga video, these Zen gardening tools, these crystals, bells, incense, statues, cushions—then you will be spiritual and self-aware. Then you will be holy, healed, and happy. After a while we add “spirituality” to our growing list of desires for good food, fine clothing, and a new refrigerator. Our hungry ghosts find no rest. It is imperative that we recognize that our particular model of civilization is actually designed to produce suffering. If we simply work harder and longer and more efficiently to make it work better—without stopping to see what we have built—we will simply produce suffering more efficiently.” — Wayne Muller

But there’s no product that keeps us away from the human condition. Just because you're feeling good doesn't mean you're doing well. There’s no way to feel permanently fantastic, to be happy all the time, to always get the good and always avoid the bad. There is an alternative. As writer Rob Breszny puts it:

“If there is any such thing as enlightenment, it arises from empathy, sympathy, compassion, tenderness, and a quest to be in intimate connection with and in service to other beings.”

In other words, if there is such thing as enlightenment, it comes from attention. But attention requires time, time where we can see everything with what St. Ignatius called “affectionate awe.” In modern society, we’re possession-rich and time-poor. Abundant in the things we don’t really need and deprived of the things we desperately do. If we want empathy, compassion, tenderness, and an intimate connection to everything, the first order of business is to find the time.

Kinship culture

According to Professor Juliet Schor, author of the book Plentitude, a cross national meta-study shows that a reduction in work hours becomes a reduction in ecological footprint. A 25% reduction work hours means a 32% reduction in ecological footprint. There is in fact a triple dividend of shorter hours:

Lower employment = lower ecological footprints = more free time, decreased stress, and increased family and community life.

The ultimate goal is kinship culture. Everyone belongs to us. We've forgotten that. I’m not any better than you in that; I feel as separate from others as anyone else. But I do believe kinship is the goal.2 Kinship with the animals, even if we choose to eat them. Kinship with those in ahead of us or behind us on the supply chain. Kinship with all of humanity, even in its most distressing forms.

As a spiritual director, I believe we spend our entire lives learning to love, and to love all things. Going back to the Gospel story above, I believe we’ll have a seat in the Kingdom of Heaven when we see kinship with the hungry, the thirsty, the stranger, the sick, and the imprisoned, not because we’re rewarded for doing so, but because in seeing and claiming our kinship with all, we create heaven on earth. Yes, heaven is a place on earth. All we need is the time, attention, and affectionate awe to make it so. If my experience with eating less meat is any indicator, it doesn’t happen all at once. It happens because we allow ourselves to feel compassion and empathy for everything we think is Not Us. But by slowly opening ourselves to tenderness, we find an intimate connection to everything.

Kinship is the source, the path, and the goal.

The meat industry lobbied for the "Animal and Ecological Terrorism Act", many states prohibit "entering an animal or research facility to take pictures by photograph, video camera, or other means with the intent to commit criminal activities or defame the facility or its owner." It also created a "terrorist registry" for those convicted under the law.

Check out my attempt at economic kinship with all, the Jubilee Fund.

This post deeply inspires me. Thank you, Douglas!

Thank you! 🙏🏽