How do we combat our tendency to take things for granted?

Antidotes to the hedonic treadmill from the wisdom traditions

After last week’s post, I’m still thinking about the hedonic treadmill: how we keep getting more and become acclimated to it, meaning we keep needing more. We keep running in place, having this vague sense of dissatisfaction that we just can’t get away from:

Has it always been this way, or is a modern phenomenon? How do we combat our tendency to take things for granted?

Gratitude

Every spiritual tradition around the world has a gratitude practice in it: prayers of thanks as a way of waking up to the gifts all around us that we in no way earned. This morning, I pulled this card from my gratitude deck:

What basic needs have you never had to worry about? Personally, I use about one thousand gallons a month in my house. How long would it have taken for me to bring 1000 gallons to my house, like people used to do before modern life? And the water is heated. By electricity. No one had electricity a hundred years ago.

Thirty years ago, no homes had Internet (I remember this!). Due to last week’s winter storms, the power went out and I went 19 hours without it. (Marlon Brando: The horror)

In the 1920s, people spent 25% of their budget for groceries. People used to spend 17 percent of their budget on food in 1960. Today, the average food budget is 11 percent, half of it spent on restaurants.

Clean air. A sense of physical safety. A pumping heart.

Start counting the things you’ve never had to worry about and you’ll soon find, to use a Buddhist and Taoist phrase, ten thousand things to be grateful for. In the East, the phrase ten thousand things means “everything,”1 which Father Richard Rohr says is just another word for God.

As the Franciscans would say, we don’t need to ask for grace. We can’t even avoid it if we tried. As Sister Mary Jo told me, we’re drenched in grace. “Everything” that supports and sustains us has been a gift.

Gratitude simply creates consciousness around it.

The golden world is there all the time, it is a misconception to think that we produce it or earn it. It is not some other place or time, but a state of consciousness, an experience open to anyone, at any time, and at any place. The Kingdom of Heaven is within. — Robert Johnson

Feasting and fasting

In addition to the Super Bowl, this last weekend was Chinese New Year. Gung Hay Fat Choy! Traditionally, Chinese New Year is typically a day of purification. Some families eat vegetarian that day, following the Buddhist prohibition on slaughtering animals to symbolize the purification of body and soul. Then you feast for 15 days, with dumplings, my favorite, being central to the menu.

When I was growing up, I remember my uncle (who raised me) would fast on New Year’s Day as a way of clearing his body and his mind. I was thinking about that after Chinese New Year and then the Super Bowl the day after. So much food!! Most of us are used to feasting: Thanksgiving, almost every holiday, birthday parties, weddings. But how many of us have a regularly fast?

In traditional cultures, both feasting and fasting were part of the yearly rituals. In the major traditional religions, people refrained from consuming any food or drink from sunup until sundown as religious practice: forty days of Lent in Christianity; Yom Kippur, Tisha B'av, Fast of Esther, Fast of Gedalia, the Seventeenth of Tammuz, and the Tenth of Tevet in Judaism; a month of Ramadan in Islam.2 As anyone who has participated in these rituals will tell you, feasting becomes a real celebration when you have fasted. But just as importantly, the fasting has its own joys: mindfulness, concentration, peace.

In modern life, we want the feast, but not the fast. It’s that the hedonic treadmill in sum? But to really enjoy the yang, you must balance it out with yin. Any Taoist3 practitioner will tell you that the root of illness is imbalance between the two.

Science has found tons of health benefits in fasting: lower risk of coronary heart disease, reduce inflammation, cell repair, and fat burning. I think of the benefits of feasting as primarily emotional: a sense of community, a sense of abundance, joy. But like we’ve pointed out, too much celebration deadens things that once were once life-giving.

You can neither fast nor feast all the time, they work in tandem. In addition to Chinese New Year and the Super Bowl this week, it was Mardi Gras. Fat Tuesday, the last celebration before Lent. Seven weeks of Lent which culminates into the traditional Easter feast.

I’d argue that Mardi Gras and Easter feast lose meaning without Lent in between. You have to balance getting with non-getting. And when you can embrace it all, you embrace God.

The sage accompanies and welcomes all that happens, both that which is arising and that which is dying. . . . This is why his joy is unconditional — Fung Yu Lan

Eating bitterness

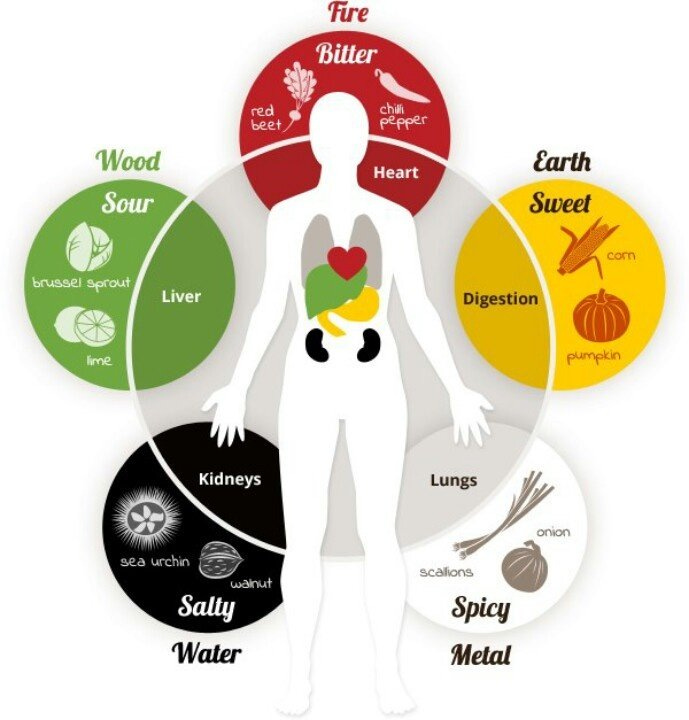

Chinese cuisine is rooted the same yin-yang philosophy: a meal must be multicolored and balance the Four Natures ('hot', warm, cool, and 'cold') and the Five Tastes (pungent, sweet, sour, bitter, and salty).

When I was growing up, my aunt used to put bitter foods on the table and tell me: “You must take the bitter with the sweet.”

She was talking about the Chinese belief in “eating bitterness” that one must accept hardship in life and learn to overcome difficulties without complaint.4 Eating bitter things is literally practice for welcoming and accepting the bitter things in life and in ourselves. Of which there are many.

We must accept the bitter with the sweet. If we keep rejecting one and keep seeking the other, how can we be comfortable in the world? But accepting bitterness is not a natural trait. Babies take to sweetness naturally, but eating bitterness is something we have to learn. But learning to accept and become friends with it all is the spiritual goal anyway. And the prize might be what thirteenth-century Buddhist priest Dōgen Zenji described as enlightenment: intimacy with all things.

Many people awaken in adulthood to a growing desire for greater self-awareness and authenticity and for a deeper intimacy with others, both of which can be achieved with shadow-work. We suggest that this awakening desire is part of a natural developmental process that occurs in adults, which has been charted in the transpersonal and spiritual literature. Unlike the transition from adolescence to adulthood, which occurs biologically and therefore automatically, the transition to greater consciousness must be chosen and then enacted intentionally. — Connie Zweig

Gratitude, fasting, and balance, all antidotes to our natural desire for more.

Unlike our desire for more, you’ve got to choose them. They all require consciousness and choice. But isn’t that the entire point?

Maybe in the way Jesus said to forgive people seven times seventy times.

Possibly Ayurvedic as well?

Eating bitterness is a cultural fault line for immigrant and first generation Asian Americans